MARTIALFORCE.COM

PRESENTS

Living Sanchin: Mind, Body and Spirit

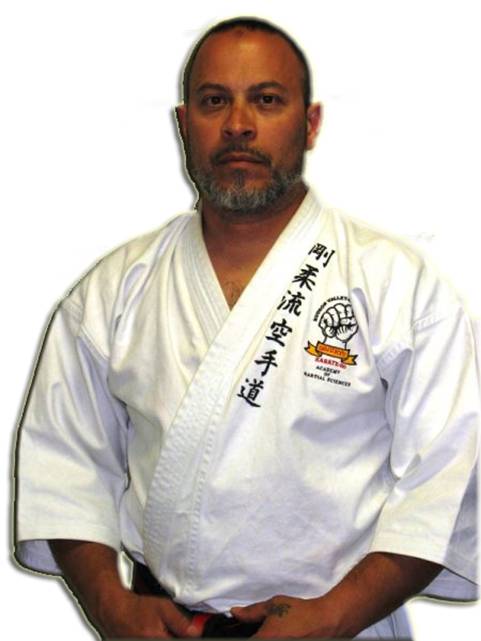

AN INTERVIEW WITH

EDDIE BURGOS, KYOSHI

Goju-Ryu Karate-Do

Jan / 2010

Founder of Hudson Valley Garden Dojo

Academy of Martial Sciences

Written by Lydia Alicea

Edited by William Rivera Kyoshi

Martialforce.com Online Magazine

Sanchin, in some forms of karate, is the ultimate breathing kata. It is also about the three battles going on between ones’ body, mind and spirit with the ultimate goal to have all three working together. In karate it is not just about a punch and it is more than hurting someone.

Kyoshi Eddie Burgos is the embodiment of Sanchin. He is living it today as he did when he trained as a youngster, later as an adult from the lessons learned, and the skills acquired. Those many steps taken when forwarding a punch, a kick or a block, have developed to work simultaneously together, in mind, body and spirit; each breath combined with movement, concentrating so that his spirit drives him to be the best at what he does each day.

Burgos is a product of an era gone by that produced an outstanding number of young, talented and fierce urban martial artists, who came up through hardcore training and life; their mark is still an influence today.

His martial arts history is impressive, grounded in the fundamentals of USA Goju-Ryu Karate-Do, trained and practiced for over 45 years, and later enhanced with other arts including Hapkido and Wing Chun. In addition, his accomplishments include:

Top kickboxing champion, winning the “Super Light-Weight title and holding it for five years.

Competed in the New York State Police Olympics in 1993, 1994 and 1995, winning four gold medals, two silver medals and one bronze.

Karate sports competitor, winning numerous grand championships while earning a place in the Sports Karate National Black Belt League (NBL).

Certified New York State Police Instructor in Police Tactics such as speed cuffing, control and restraint, weapon retention and take downs.

Certified official for the U.S. Kickboxing Association.

Kickboxing and mixed martial arts instructor.

Founder of the Hudson Valley-Garden Dojo.

Here is our interview with a living legend, Kyoshi Eddie Burgos.

Martialforce.com: Let us start the interview at your beginnings. Where were you born? Where did you grow up?

EDDIE BURGOS: “I was born and raised in Manhattan, New York. My family and I lived in Spanish Harlem in one of the public housing projects called, ‘The Johnson Houses’ located at 115th Street and Park Avenue, across from ‘La Marqueta (The Market).’

Martialforce.com: You mentioned beginning your study of karate at the age of five. That is very young, how did this come about?

EDDIE BURGOS:" My parents were divorced when I was in the second grade, and my father was not around to help us or have an impact on our upbringing (two brothers and myself). My brothers and I grew up in a time filled with racial tension and as a result, were often picked on. My mother was a weekly mugging victim because people knew she was alone, with no male adult at home.

One day I watched a Judo class at the Spanish Harlem Boys Club. It definitely caught my attention. I began classes there and continued for about six months until another time, I saw this crazy looking art that encompassed kicks instead of flips and throws. It was Sensei Billy Rivers class and what I was watching was karate. It looked scary as hell so I never returned. That is until I watched “The Green Hornet” (a television show back in the late 1960s). I realized that what Kato was doing was the same thing. I later returned to the class, wanting to learn more about this weird deadly art of Kato, so I could get back at my mother’s muggers.”

Martialforce.com: Was Sensei Billy Rivers your first instructor?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Officially, yes. However, his students (my sempais) were often teaching the class. They were Dennis Melendez and Cha-Cha. When Sensei Billy Rivers taught, instruction was harder, longer and painful. I would return home too tired to eat, just bathed and off to bed.”

Martialforce.com: Did you seek him through the NYC Boy’s Club chapter in East (Spanish) Harlem?

EDDIE BURGOS: Yes, because it was the only place in Spanish Harlem that I knew of that had martial arts classes at that time. I attended instruction every Tuesday and Thursday from 5PM to 8PM.”

Martialforce.com: For those readers, who are not familiar with the Spanish Harlem of that period, describe it.

EDDIE BURGOS: “Oh boy, this might sound a little bit out of a Hollywood flick. It was a scary place and time to be living in. Many of the tenements were either burned down or falling apart. The biggest problem was the pervasiveness of drugs, particularly heroin use. It was everywhere and it seemed as if everyone was into it. The other reality was gangs. They were rampant in every corner, every block, in every backyard, roaming predators. One had to be extremely cautious when walking through these areas because they were always hanging out on some corner waiting to mug you or just beat the hell out of you if they thought you belonged to one gang or another. If that was not enough, there were the racial conflicts that turned into fights in the schoolyards, playgrounds or on the project grounds. I was too young to help my brothers and Mother, and without a father or an adult male at home to protect us, we were often picked on.”

Martialforce.com: Describe if you will, your early memories of learning karate at age five. How did it affect you?

EDDIE BURGOS: “I recall often daydreaming as I watched Sensei Rivers perform his skills. It overwhelmed me. I would watch in awe as he put some of the other classmates (adults) down with a reverse punch, leaving them to lay on the floor gasping for air. I just visualized in my mind using those same techniques to get revenge against the muggers and those who abused my brothers and me. It never happened.”

Martialforce.com: Describe your training under Sensei Billy Rivers.

EDDIE BURGOS: “As I mentioned earlier, Sensei Rivers did not teach often, but when he did, it was harder and more painful. We did a lot of conditioning and sparring (Controlled Fighting) from the corners. One of the advanced students would take the center of the square and he would scream at us to attack him. He then proceeded to wipe the floor with us. Looking back now it was not so bad. It taught me to be tougher.

When I was young, my mother would take my brothers and me to visit Puerto Rico every summer. It was her way of protecting us from the horrors of the streets for three months of the year. After the summer, when I returned to the dojo I had to start all over again. This went on for quite a while and I became the most experienced white belt in the dojo. I never did advance to yellow belt under Sensei Rivers although I did learn the kata required for the rank. Rivers never granted rank easily, he was very tough. The greatest lesson I got from him was the importance of practice and the rewards of practicing harder.”

Martialforce.com: You later began attending another dojo at the “Taft Housing Community Center” where you met and began studying under Sensei Walter Johnson. How old were you then, and what attracted you to him? Describe your training under Johnson.

EDDIE BURGOS: “I was about eleven years old. During a field trip to another dojo (Training hall) at the Taft Housing Community Center, I met Sensei Johnson. It surprised me to learn that the dojo was located closer to my home than the Boys’ Club. Heck, I could just cross the street where La Marqueta was and be on the same block as the dojo.

I was struck by his size and amazed by his ability to move with grace and quickness. His techniques were on target every time. Yet, it was his gentleness and kindness that impressed me. He was tough on his students but not overbearing. He had an air about him that I never seen displayed by anyone else in Karate. I figured, if I can study with him for a while and learn something, then maybe Sensei Rivers would take notice and finally promote me. After a year went by, Sensei Rivers told Johnson I was his student. One day, Johnson approached me and I admitted being Rivers’ student. I then asked if I could remain in his school, which he allowed. I was 12 years old at the time.

Training with Sensei Johnson was just as hard as with Rivers. In fact, it seemed as if they were from the same tree; they were part of the “Harlem Union,” all students of George Matthews, a student of Grand Master Peter Urban. Walter Johnson was the highest ranking amongst them and they went to him to learn kata.

As I became older, training with Sensei Johnson got increasingly intense. While as a green belt (13 years old), I was responsible for teaching the peewees and later practiced in the junior and the intermediate level classes. I would begin around 4PM and end at 8PM. At brown belt level, (14-15years old) Sensei would have me teach the peewees, and practice in the junior, intermediate and senior classes. I had to do perform Kata, Ippon (Techniques) and Kumite (Sparring) in each of the classes and did not finish until 10PM. It was very exhausting yet it felt good. I did them three days a week. Sensei would go over the kata with me several times and have me demonstrate at events. We conducted Saturday morning classes from 8AM until 11AM during the summer months and competed in tournaments just about every month. Sensei was a strong competitor, often bringing home the “Gold” in the heavyweight division and I second or third, but always the bruises! Tournaments in those days were no joke. I usually placed in kata too.”

Martialforce.com: You remained with Sensei Walter Johnson until the age of sixteen when you earned your black belt. Describe your shodan (First Degree) grading.

EDDIE BURGOS: “Sensei took us to a dojo in the Fordham Road section of the Bronx for my shodan grading. I remember it being a long testing day, on a Saturday, which began at 9am. My mother sat in the audience busting with pride, knowing well that it was karate that saved me from the streets. She was also grateful for Sensei Johnson’s influence, which kept me straight and on track. Heck, she was so overwhelmed by the event that she forgot to take pictures! She managed to take two, one of me sparring and the other of me receiving my black belt. Today, we still laugh about that and I never let her live it down.

For the grading, I needed to demonstrate that I knew how to conduct a class, perform all of my kata with full kime (focus), spar with everyone in the dojo that day, including Sensei. I also demonstrated my ippons, broke boards and even bricks. On that day, at age sixteen, I was promoted to Shodan.”

Martialforce.com: At age seventeen, you enlisted in the Army. At some point during this time, you began to study other art forms, Taekwondo, Hapkido and Wing Chun, each of which is very distinctive. What was the attraction for you and how far did you advance in each?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Let me first explain why I enlisted in the Army at age of seventeen. I was a junior at Aviation High School in Queens. During the previous two years, I was getting into too many street fights. The school officials advised me that I needed three credits to graduate, and if I could hold out to retake the music lecture class that I failed, I could graduate with my class. Unfortunately, I was again, picked up by the police for fighting and brought before the same Criminal Court Judge, as three months previously. The Judge presented me with a difficult choice, to either enlist in the Army or go to jail. I chose the Army.

During basic training period, instructors had to teach the recruits hand-to-hand combat techniques. I found theirs amusing; it must have been obvious to them because they ordered me to come in front of the company and told if I knew better techniques than they, to teach them. I did, and for doing so, it helped me graduate from basic training with rank advancement.

During my training in the Infantry School, I practiced my kata in secret, recalling what Sensei Johnson said prior to my departure, “To study your kata, for the secrets of Goju are in the kata.” I did not know what secrets he was speaking about despite thinking I knew it all.

I was assigned to the 1st U.S. Calvary Infantry Division-2/7 Garry Owens, Air Mobile Unit at Fort Hood, Texas. Soon after I arrived to Fort Hood, I was introduced to other arts that were worthy of learning, after I overcame some of my prejudices of certain martial arts. I met Master Wong Soo Park, a Korean who spoke little English. My only reason to be with Master Park was so I could use his dojo to practice in. He granted me permission so long as I taught his class every so often. For two years, I learned Korean Taekwondo from Master Park. I did learn the forms of his style and he advanced me to Nidan (Second degree) level, but I never really got into his Tang Soo Do. Perhaps it had to do with my prejudices again.

Master Wong Soo Park later went on to become head of the Tang Soo Do system in the U.S. He held several tournaments, which I took part in. I placed several times in the Black Belt division.

While at the dojo in town, I met several solders that were looking for a practice partner. They did not want to share their practice with Master Park, so they asked if I would join them at the gym on base. I was glad I did.

From them I learned the basics of Hapkido and Wing Chun. We taught in rotations so we benefited from each other. My initial feelings of these arts were negative due to my bias, feeling I had trained in a superior art. Shortly after, I learned that these arts had more to offer me than being different, something I could pull from and combine with my Goju. We practiced together for two years, one of the best learning experiences of my life.

When I returned home to New York, I realized that my Goju had forever changed because of what I learned from these arts. I recall a day when Sensei Johnson put me up against one of my classmate’s student, a Nidan. Every time he went to throw a reverse punch, I would block and sweep it under my arm, bringing it into a lock. As he tried to spin in the opposite direction in an attempt to escape and deliver another reverse punch, again I blocked and trapped. This happened twice. When asked how I was able to execute these forms, I shrugged my shoulders and stated that it happened by instinct. My dojo brothers went into a furious discourse as to the hows and ifs. They felt that if I could not explain how I accomplished the technique then I never mastered it. Yet, Sensei saw it otherwise. He explained that the technique became a part of me and hence I could not justify how I accomplished it although able to demonstrate it twice. Sensei also added that I knew the technique without knowing the why and that I should attempt to break it down in order to have a better understanding of it. Immediately I was promoted to Nidan.”

Martialforce.com: Kyoshi, after some time had past, you developed an interest to combine what you had learned from the arts with boxing. Tell us about this. Were there influences at that time?

EDDIE BURGOS: “It was in the late 1970’s and I was working locally at La Marqueta selling cosmetic goods, health & beauty products. I was also back to fighting in the streets, only this time against thugs, purse-snatchers and muggers. After a former brother-in-law began to get into boxing, I thought a lot about the idea of combining boxing with Karate. One day, the brother-in-law and I went to a gym located in the housing projects. There I met a man named, Negro. Just from looking at Negro you could tell that he knew his boxing stuff. He took one look at my knuckles and asked if I ever boxed before and I responded no. Negro insisted saying that my hands were fighter’s hands I must have boxed before. I reassured him that I never boxed, but I did not volunteer to him that I was a martial artist.

A little while after the meeting, I asked him if I could kick the bag, and he said sure, but I had to do it barefooted because he did not want the bags ripped open by kicks. Gradually I applied the boxing techniques he showed me and combined them with kicks. He stopped me and said, ‘I knew you were a fighter, I saw it in your knuckles, and you do kickboxing too.’ I thought, ‘What a great term, kickboxing,’ thinking I had stumbled upon something new! What I did not know!

Negro went on to tell me about “Wildcat” Molina and “Apache” Cruz, suggesting I should come down on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays to watch them train and I did. I had known about “Wildcat” and “Apache” before I entered the Army. “Wildcat” was Billy Rivers and Walter Johnson’s dojo brother. I also knew about Apache’s reputation on the street.

I would definitely say that Wildcat and Apache were both strong influences. Soon after we met, I began training with them, learning the concepts of kickboxing, or better yet, full contact karate. Grand Master Aaron Banks promoted most of our fights, and later on, Louis Neglia began promoting us under the International Sport Kickboxing Association (I.S.K.A.) We formed a team, with Apache as head fighter, Victor ‘Hammer Hand’ Morales and me, and Wildcat Molina as our trainer.”

Martialforce.com: After you left the Army, you returned to New York and began teaching in an after-school program at JHS 117. Did you teach students more than just karate?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Apache was teaching in a community program for kids. I was in need of a job so one day Apache introduced me to “LUCHA” and its staff. An after-school program was starting up and it needed a karate instructor. Apache referred me to the program managers for the position. I got the job and given a great opportunity to make a living doing, what I loved most. It also afforded me time to train for my fights with a fan base. As I taught, I was able to interchange between traditional and full contact training without a problem. I saw it as just another means to expand my training and learning. The traditional kata training helped with breathing and footing, while my full contact training improved my stamina and striking.

I taught traditional karate; however, the sparring was geared more towards freestyle than traditional kumite. I taught the ippons, but with a little more adherence to street fighting. I guess this was when I started to mix my arts.

One day Sensei Johnson came by and sat down to watch. He later commented that I seemed to have found my way to teaching something valuable, but advised me to continue practicing and learning from my kata. He then invited me to the dojo for lessons. He later promoted to Sandan. Soon after, we had our fall out and I never returned to his dojo.”

Martialforce.com: As you mentioned previously, you began your kickboxing training under “Wildcat.” Can you discuss it?

EDDIE BURGOS: “I knew of Wildcat prior to the kickboxing. He had a reputation on the street, as did Apache, but also in the martial arts arena. They were respected and feared. People asked if I had lost my mind joining up with them, I just shrugged and went with it.

We competed, traveling up and down the East Coast, taking fights on a last minute’s notice and bringing home the Gold. We were undefeated for a long run.

Many fighters felt our wrath as we competed in various regions, taking what we thought was ours to own. We were good because all we did was train. I tell you, during this time, I was definitely in the best shape ever of my life. Not even the U.S. Army got me into better form than Wildcat Molina did. He would break you down and rebuild you. We would begin with floor work, the bag, shadow, jump rope, floor exercise and then ring work. We would do a minimum of five 3-minute rounds of each. That was until the ring work came along. If you were scheduled to fight three rounds at 2-minute each, you did seven rounds of sparing at 3-minutes. We would do these four times a week. Then for a break, it was a three mile run every other day, except Saturdays that is until we met Wildcat at the reservoir in Central Park and do the damn thing three times around, and every so often at full speed.

It was not until after twenty nine bouts, and when Wildcat retired from the kickboxing, that I began to slip in my training. I was working with the City of New York Parks Department, Parks Enforcement Patrol (PEP). I was in the Mounted Unit and my interests took different turn. My second to last bout ended in a draw and I lost my last one by 1 point by the judges. I decide it was time to move forward. I retired from kickboxing in 1989 with a record of 27-2-1.”

Martialforce.com: After you had earned your 3rd degree from Sensei Johnson, he expressed resentment towards your kickboxing. Why did this upset him?

EDDIE BURGOS: “When I began competing, after having fought three bouts and winning them, I returned to the dojo for traditional training. By this time, the word was out, I was doing full contact karate and I was on Wildcat’s team. Sensei did not say anything about it at first. It was some time after my promotion to Sandan that he over heard me say something about full contact karate being closer to reality than traditional karate. In that moment he blew it, yelled at me from across the locker room and stated that if I wanted reality to come back into the dojo and he would teach me reality. He added that I was naïve about what karate had to offer if I thought that full contact karate was closer to reality than traditional karate. I believe our disagreement had more to do with my being with Wildcat. There was bad blood between them. I never learned why.”

Martialforce.com: You have provided great insight into your beginnings and the paths you chose. Let us take a different direction and discuss “Reality-Based Training.” From your prospective, explain how it applies to martial arts training.

EDDIE BURGOS: “It is an interesting concept and it seems everyone wants to jump on this one. The fact of the matter is unless you have never been in an actual physical confrontation you will never know what reality-based means. Today you can open many martial arts magazines and read about reality-based martial arts. Today, everyone professes to be an expert in this area. Some attempt to teach reality-based training to people using military tactics. Yet, that is not reality. How many people do you know carry an AK-47 or a shotgun? Better yet, how many are walking in jungle fittings? Since 911, many have chosen to play on the public’s fear and its perception of what represents a threat, all in order to capture an audience. In everyday life, how many people will actual deal with a terrorist? For the most part, the public will avoid any such confrontation and leave it to law enforcement professionals. Instead, reality-based training’s focus should be to teach the public how to spot a danger, avoid it, and report it ASAP.

I think a better question is what should reality-based training be to the martial artist? The answer includes and is not limited to:

To use your training in a way that will assist teaching how to hit without pulling back a strike. The only means of control is placing the technique where it is meant to be, for full damage.

To build the psyche to go through the offensive without hesitation.

Learning the legal ramifications of your actions once, you decide to use your art for self-defense.

Training with full protective gear and actually applying the techniques with resistance from your partner.

Practicing Bunkai Oyo at full speed without cooperation from your partner.

Learning to observe and use the environment.

Always being on your guard.

Learning to improvise with whatever means you have in your hands, as Maestro Peter Urban would so often suggest.

A martial artist has to know his/her weak points so it is important to improvise for them. Learn the weaknesses of the body, the striking points, angle of attacks, proper stances and the psyche of the fight and fighter. There is so much to be said about reality-based training that it would take an entire book to explain.”

Martialforce.com: Our research shows that law enforcement authorities in California as well as in other states, require instructors to participate in P.O.S.T. (Police Officers Standards in Training) in order to teach officers. You are a police tactics instructor as well as an experienced martial arts teacher. My question is, while you hold rank in Goju-Ryu Karate Do, are you required to hold some type of law enforcement certification to teach and why?

EDDIE BURGOS: “In the State of New York, to be a qualified instructor, one must obtain certification from The New York State Municipal Police Training Council. You become a “General Topics Instructor” and then train as a “Defensive Tactics Instructor.” My Nanadan (7th. degree black belt) in Goju-Ryu, or any other style would have no bearing what so ever in requiring certification.

The reason for requiring certification is due to “Vicarious Liability,” a law that forces the hand here. The department and instructor are legally responsible for the techniques used, even if sanctioned. This is “Vicarious Liability.” If police departments allow any martial artist to teach the skills, without taking into account the “Use of Force Continuum,” then we would be no different from the thugs we try to subdue. The benefits of being a martial artist, as well as teaching police defensive tactics are using the techniques and seeing its effectiveness.

The main objective of the defensive tactics instructor is to implore all possible physical control alternatives to the firearm. Once deployed, the firearm cannot call back the bullet. With defensive tactics, the option of escalating and de-escalating the force remains. The other objective is to achieve the goal using as little force as possible or as much is necessary to subdue the perpetrator, a task the general martial artist does not train for. Most train either for Sports Karate, which is of little use in actual police tactics, or for self-defense, which would go beyond the scope of the force continuum. In the State of New York, officers have to refer to Article 35 of the Criminal Procedure Law.

There are certain arrest techniques and defensive tactics training criteria departments must adhere to, without overstepping the line of excessive force. Law enforcement departments are liable if personnel are trained improperly. On the other hand, if an officer exceeds that boundary, then he/she is criminally responsible. The sad thing is that most departments do not train officers after the initial academy exposure in this area, nor do they allocate enough funding to teach defensive tactics besides the deadly use of force.”

Martialforce.com: With the need for specialized training in law enforcement, are your methods applicable towards police instruction?

EDDIE BURGOS: “There is a completely different level of teaching law enforcement when it comes to defensive tactics. The objective of law enforcement is to bring the perpetrator to justice, while the purpose of civilian law is to ditch out justice. Criteria vary greatly here. In retrospect, teaching law enforcement has changed the way I teach civilians.

There is what I often refer to as the ‘theory vs. reality’ of teaching. For example, in martial arts schools, students are conditioned to punch, block and counter (ippon) in a more robotic state, reflecting certain moves from either kata or the Sensei’s (teachers) imaginations. Most of that robotic type of training stems from numerous theoretical possible attacks. It is just not practical to encompass all possibilities in a lifetime without actual experiences, reality.

Law enforcement focuses on subduing, restraining and controlling the perpetrator, unlike civilian training, where most schools teach no first attack. Law enforcement must induce the first move in order to prevent further adverse responses or injuries. Hence, law enforcement must be pre-emptive, together with the fact that civilians have the obligation to avoid and retreat from confrontations; law enforcement does not have that option. Teaching law enforcement is slightly different. I use the concepts of ‘Force Continuum, Control and Restraint, and Pain Compliance.’ In civilian classes, I teach the legal ramifications of potential actions, along with theories of closing the gap, causing an imbalance and striking the vital area, along with run like hell and do not look back. In both classes, I teach a theory, conceptualized as ‘Quartering the Body.’ I am working on putting that theory into a book and DVD format.”

Martialforce.com: Do you feel that your experience as a police officer helps you to know what officers in training need?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Absolutely, law enforcement has a culture unto its own. Knowing the mindset, culture and expectations allows me to gear the training to fit the criteria of the department(s) and be more specific to the officer’s need. Teaching force continuum, control and restraint, pain and compliance and weapon transition is a challenge for any instructor.”

Martialforce.com: Do you think it is important for a police officer to have good tactical communication skills (verbalization)?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Often, verbal commands are the first line of defense for law enforcement and civilians. Being able to talk down the resistance is an art. Many departments teach Verbal Judo a skill worth having. If we can have a person submit without having to resort to physical confrontation, then the objective is accomplished.”

Martialforce.com: Do you find that police officers are receptive to martial arts training?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Some officers are yet others feel it is too much work. If a department does not mandate the training, many will not attend. You find that the ones that do attend voluntarily are the ones that care about themselves, want to stay in shape and be safe. If it were up to me, all law enforcement personnel would be required to enroll in some form of martial arts training. It is not just about kicking, punching, blocking and arm bars. It is about building the person’s confidence and establishing a person’s proper demeanor.”

Martialforce.com: Do you teach the use of force continuum and can you give us an example?

EDDIE BURGOS: “I believe strongly in the concept of use of force continuum, not just for law enforcement but for civilians as well. As mentioned previously, the law is finicky. Article 35 of the State of New York which is the “Criminal Procedure Law,” clearly defines whom, when and how in the use of force implementation.

The criterion for the use of force differs between the civilians and officers. Civilians are compelled to avoid and evade confrontations if possible. If the need to use force were to arise, they can only use the amount of force to stop the attack and then cease to use such. Law enforcement officers do not have the option to avoid or evade. They have to confront the conflict. How they confront or approach a conflict depends on many variables. The first approach should always be verbal tactics, better know as verbal judo. This along with a commanding posture is a show of force and may be enough to reduce the level of conflict. It is imperative that the escalating level of force be dependent on the actions of the perpetrator. The officer by his/her own accord should not determine the level of force he/she is going to use to handle the conflict. Officers should never allow the escalation of force without ever having the possibility of de-escalating.”

Martialforce.com: “Do you enjoy teaching police officers?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Teaching law enforcement is challenging as well as rewarding. Caution is the best advice I can offer any instructor contemplating taking on the task. If their teaching methods do not encompass the use of force continuum, control and restraint and pain and compliance, then it is best that they learn these first. The rewards are plentiful.”

Martialforce.com: Do you practice and teach Kobudo (weapons)?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Yes I do. My personal favorite is the Sai. I find that practicing with the Bo, TonFa and Arnis (sticks) are particularly helpful for law enforcement. For example, the Bo can substitute into the use of the straight baton, the Ton Fa with the PR24 and the Arnis with the expandable baton. I enjoy Kobudo because it helps to strengthen the hands and extending the mental facet of the martial artist. It also assists in the art of improvisation.”

Martialforce.com: You also teach a self-defense program for women and children?

EDDIE BURGOS: “Yes, the program I founded is called “Women against Rape & Robbery/Preventing Abduction of Children, (WARR/PAC). Its’ goal is to teach women and children self-defense techniques in order to stop an attack. This is a course where the law of justification use of force is taught as well as the ramifications on the misuse of force. It is not geared towards sports or as a combative arts study. It is simply a self-defense class that will teach about one’s surroundings and how to seek all possible means of avoidance and escapes.”

Martialforce.com: We at Martialforce.com wish to thank you, Kyoshi, for the interview and your contributions to the martial arts as well as to your work in law enforcement.” We wish you much success in all your future endeavors.

To Martialforce.com