MARTIALFORCE.COM

PRESENTS

AN INTERVIEW WITH

SHIHAN JUAN PEREZ

Interview by William Rivera and Eddie Morales

Martialforce.com: Let us start at the beginning as they say. Where were you born and where did you grow up?

JUAN PEREZ: I was born in Manati, Puerto Rico, came to the United States as an infant, raised and live in Paterson, New Jersey. I “LIVED” in C.C.P. (Christopher Columbus Projects, affectionately dubbed “Chocolate City Projects,”

because it was predominately blacks), Brook Slope Projects and the mean streets of Paterson, (mainly Madison Street A.K.A “Mad St” & Beech St). I say “LIVED,” because not too many of my friends made it out alive. My friends

often make fun of me, because they said I’m the first Puerto Rican they know that doesn’t speak Spanish or carry a knife.

Martialforce.com: Is there a word, quote, or saying that you would use to describe You?

JUAN PEREZ: “There is no one word, quote, or saying that can best describe me, because I have many roles in life that I have to adhere to accordingly. If you ask me as a Karate-ka (practitioner) I would say “student,” because I am

first and foremost a student of the art. With almost 40 years of experience in the art I am still learning, and the more I learn, the more I realize how little I know.”

Martialforce.com: At what age did you tap into an interest in the martial arts, what drew you?

JUAN PEREZ: As a kid growing up on Mad St, my big cousin (Miguel “Bebe” Cortez) and I would watch “Lucha Libre “(Spanish wrestling) then “play” wrestle afterwards for hours. At times, he would kick box me with combat boots

on. He was much older and bigger than me, so obviously he took it easy, but one time he accidently kicked me in the head with those combat boots and almost knocked me out. I ran crying to my mommy, and he caught a

whopping for it by his parents. I was only about eight years old at the time and have no shame telling this story. Nevertheless, all those times I took it as we were just rough house playing, but little did I know he was actually

training me to fight. He began pitting me against his friend’s little cousins and they would bet money on us. Friday’s became “Friday Night Fights” in my hood. We would fight in a concrete fenced area in front of my house with no

gloves on. I had a lot of success in the beginning and my ego exploded, but it was mostly against mal-nourished, or pudgy little fat kids. Then one day I faced a skinny black kid called “Lonnie.” Mad St. was predominately

Hispanics, and Lonnie came from Essex Street, which a black section of town. Even though he was skinny he was much taller than me. Lonnie toyed with me and picked me apart with his jab, then broke my nose with a straight

cross. He obviously has had some formal training in boxing. All I remember was laying on the ground with blood all over me and my cousin putting a penny on my forehead. When I came to my senses I asked my cousin, “Why is

there a frickin’ penny on my forehead?” and he said, “To stop the bleeding.” Needless to say, it didn’t work. Weeks afterwards, I had another fight with a Puerto Rican dude called “Gringo,” he was called that because he looked like

white boy. He was much bigger and older than me, this time we fought with boxing gloves and he promised to take it easy on me. He hit me with a body shot that knocked the wind out of me and uppercut that busted my nose

again. That was the last time I fought in these “Friday Night” fights. I never saw Lonnie again and I don’t know what became of him. Last I heard about Gringo, he and his brother got into drugs and both ended up dying from

AIDS. As for my cousin Bebe, someone slip a pill in his drink at a house party, he began tripping and never recovered. He’s been hospitalized in mental institution called Grey Stone in Morristown, NJ for over 30 years now.

Nevertheless, after those two-memorable butt whooping’s I really wanted to know how to fight, but I did not have the means, finance or access to any formal training.

Martialforce.com: At that time, as well as today, people’s immediate perception of the martial arts is one of violence. Was this the case with you, and if so was this the appeal?

JUAN PEREZ: As a youngster, I was attracted to the martial arts for its pure brutality. Martial artists were viewed as these invincible warriors who can break bricks, dodged bullets and do cool tricks with their bodies, and I wanted to

be like that. As I got older, I fell in love with its philosophical values and realized that those physical goals have no substance. My perception of the martial arts is that it is “a way of life” with moral and ethical principles. Sort of

like a religion, but without the worshipping of any god, unless one chooses too.

Martialforce.com: Who was your initial instructor, influences and what system did you study?

JUAN PEREZ: My cousin Bebe was perhaps the first person to teach me some type of unarmed combat. He didn’t have any formal training and was just making up stuff as we went along. However, when I lived in Brook Slope Projects, a

neighbor of mine called David “Heavy” Lawrence had just got out of some adolescent detention center. There, a staff member (I believe his name was Bernard) had taught Heavy and some of the detainees the martial arts as a form of

discipline. One-day Heavy saw me and a couple of my friends play fighting Karate and asked us if we wanted to learn real Karate. Ecstatic, we all exclaimed, “Hell Yeah!” Shortly thereafter, he began instructing us in something he called the

“KA” system, which later in life I came to discover was not. It was actually something he made up and just gave it that name, because it was a well-respected system from North Jersey. Heavy’s brand was more Kung-fu than Karate. In fact, we

all took a bus to New York one day to 42nd St. to purchase Kung-fu uniforms to train in. We had no free-standing building to train in, so we train outside, usually in the parking lot of Buckley Park’s baseball field. Training consisted mainly of

sitting for long periods of time in Kiba dachi (horse stance), knuckled push-ups on gravel, elbow form number one, and lots of sparring. We organized ourselves into a small gang called the “Young Dragon’s.” The group didn’t last long, as

winter came and we had nowhere to train. Many of its members moved, got into drugs, joined other gangs, or simply lost interested. Of the dozen or so members it had, only I and Heavy’s top protégé Darren “Robot” Woolridge remained in

the martial arts till this day. Heavy ended up getting incarcerated several times afterward. He’s out now and alive, but not doing so well.

Sometime afterward I join a boxing gym in South Paterson called Lou Costello. It was only 5 dollar a year, so my parents could afford it. My first day at the gym they put me to spar with a guy who joined up the same day I did and I put a

whooping on him. The next day they put me in with a more experience boxer who returned the favor. I guess they wanted to see how tough I was or if I was worth training. I must have not made the cut, because thereafter, I pretty much

trained myself. I liked boxing, but I got turned off with the coaches. They only focused on the professional or naturally gifted kids. On a wall hung a sign telling the boxers what to do:

· Three rounds Shadow boxing

· Three rounds on the heavy bag

· Three rounds on the speed bag

· Three rounds of Jump rope

· Calisthenics

Every day I would do it, but no one would ever correct or coach me. Till this day, I do this work-out when I work-out alone, except I kick box and don’t rest between rounds. One day a kid I knew from when I lived on “Mad St.” came

to the gym to spectate. His name was Adriel Muniz and rumors had it he knew Karate. We greeted each other, and talked for a bit. In the gym a Puerto Rican kid called “George” was working out. George saw us talking and gave us

a look that can kill. George was an outstanding amateur with multiple titles under his belt. George saw us talking and gave us a look that can kill. I thought to myself “What was that about.” Adriel asked me if I knew him and I said “Yeah,

that’s George” then added “He’s one of our top amateur.” Then I told Adriel I need to get back to my work-out and I’ll talk to him later. I was hitting the heavy bag and George came behind me and taps me on the shoulder. He asks me for

Adriel names, which I gave and then asked if I wanted to spar. Sensing he was upset about something and wanted to prove something, I didn’t entertain the idea. In reality, I knew I was no match for him. George ended up taking his

frustration out on a heavy bag next to mines. When I went to the locker room to change, I found out from the other guys in the gym that Adriel and George had a street fight in front of East Side High School about a week ago and that Adriel

beat him up pretty bad. When I left the gym, Adriel was outside waiting for me. We talked some more and he wanted to see what I’ve learned in boxing, so we began slap-boxing (boxing with open hands). Surprisingly, I held my own and after

a couple slaps each, we laughed, hug, then went our separate ways. Weeks later I ran into Adriel again at the Boys club. He wanted to slap box again and this time he humiliated me in front of a large crowd. Something about getting slap in

the face is more humiliating than getting punch. Needless to say, we did not hug afterward, as we did in our first encounter.

From Brook Slope Projects, my parents split and we moved back to “Mad St” to go live with my mom’s parents. The YMCA on Ward St, which was only a couple of blocks away from my house, was advertising “Free Karate” classes. So, I signed

up. The instructor was Joe Jimenez. It turned out to be Tae Kwon Do and not Karate, but I didn’t know the difference at the time. Training consisted of mostly kicking, sparring and knuckle push-ups. One training sessions Adriel and another

guy called Charles Jeter were spectating. Afterward, they approached me and Charles began criticizing the style I was practicing. Adriel stood there silently. I was a bit confused; because I knew Adriel did Karate, and Charles was sitting there

bad mouthing what I thought was Karate. So I turned to Adriel and said, “But don’t you do Karate?” He said, “Yeah, but I do Shotokan and what you are doing is not even Karate, its Tae Kwon Do.” I didn’t even know there was a difference.

The flyer advertised “Free Karate.” Then they both went on explaining and showing me the difference. The low stances immediately attracted me and I told them I would like to check out their school. Adriel agreed to take me, but every

time we arranged to meet, he stood me up. I’ve always wanted to join a karate school but my parents couldn’t afford it and now that my mom was a single parent those dreams were even dimmer. Then one summer I got a job through a

youth program called C.E.T.A. (don’t known what those letters stand for). Anyway, I started working for some Latin organization called Aspira. My job entailed running errands, cleaning and clerical work. A month later I got my first check,

cashed it and then tracked Adriel down to take me to his school. He finally did and with the cash in hand from my first check, I enrolled myself in a Karate Dojo (school). The Dojo was called “The House of Shotokan” and it was on Main Ave

in Passaic, NJ. The instructor was Seifullah Ali Shabazz. Shabazz is a unique individual. He’s a black soul trapped in a white body. He’s an American born, Red-headed, Caucasian, Muslim; a devoted follower of the honorable Elijah

Muhammad. His strong views of the injustice of blacks and minorities around the world profoundly influenced me. His individuality, taught me “dare to be different,” which is a trait I’ve instilled in my own kids. Shabazz once said to me, “If

you’re going study something you must study it deeply.” Ever since then, I’ve been researching my art. Nevertheless, I was surprised to discover that Charles Jeter who tried to project himself as an authoritative figure on the martial arts was

only a white belt who no longer attended class. Adriel Muniz on the other hand was an outstanding brown belt at the time. Shabazz studied under Toyotari Miyazaki of Flushing Queens, N.Y. and taught Okano-ha Shotokan-ryu. Okano-ha

Shotokan-ryu is the Shotokan style of Tomosaburo Okano, who was Miyazaki’s instructor. Okano was a disciple of both Yoshitaka “Gigo” Funakoshi and Gichin Funakoshi, though he primarily trained under Gigo. I’ve heard his style referred

to as:

· Shotokan

· Shotokai

· Gigo Karate

· Kenkojuku (Shotokan)

Nonetheless, it is Shotokan. There is a misconception that there is only one type of Shotokan and that it is J.K.A. (Japan Karate Association) base. My research (via books and internet), led me to discover that there are fundamentally 3

variants of Shotokan, which were developed during the following eras:

· Pre-WWII

· During WWII

· Post WWII

The Pre-WWII Shotokan has been described as a Japanese Shorin-ryu, or as some has put it “Shorin-ryu on steroids,” and is the Karate Funakoshi first introduced into Japan. WWII Shotokan was Okano’s and that of the Shotokai. Post WWII

was JKA Shotokan. Though all three versions were technically cultivated through all the eras, they made their biggest impact during those eras. As a side note, Okano’s Kenkojuku organization pre-dated the two Major Shotokan Organizations

(Shotokai & J.K.A) in Japan by several years.

Like most styles of Japanese Karate, training with Shabazz consisted of the 3 K’s:

· Kihon (basics)

· Kata (forms)

· Kumite; Ippon gumite (one step sparring), Jiyu gumite (free sparring) and Enshin gumite (circle fighting)

Adriel became my best of friends and we often trained together outside the Dojo (school). We were young teens at time, and neither of us had a car or license. We usually bused to the Dojo and at times fell asleep and woke up at the last

stop, which was the Port Authority in New York. Whenever I didn’t have bus money, I would jog to the Dojo with my knapsack; take class and then jog back home. Passaic is two towns over from Paterson, so it was quite a distance. A few

times I got stop by the police when I jogged through Clifton, which is the town between Paterson and Passaic, and predominately white. After a quick interrogation and frisk I was able to continue my run. This angered me, but I was able to

channel this anger through my run, or in training. On one such occasion, an officer stopped me and asked me where I was running to and when I told him, he asked if I knew who he was, I recognized him from the Karate scene and answered,

“Yeah, you’re Pat Ciser from Koei-kan.” He didn’t bother frisking me and told me to enjoy my run and send my instructor his regards. From that point on, I never got stopped again jogging through Clifton.

As an affiliated Dojo of Miyazaki, we were permitted to train at his Dojo, which we did every Saturday. We also had to test under him in his Dojo in front of a board. Shabazz began his teaching career as a blue belt, and by the time he reached

black belt he was a seasoned instructor. It was evident he knew what he was doing, as all his students were well accomplished and did very well in test. I tested under Miyazaki twice and got skipped from white to blue and blue to purple.

Aside from being nervous, I found testing easy, as it was the same exact things we did in class (The 3 K’s), except we got to rest in between the groups that were testing. At times, Shabazz would be very hard on Adriel and me, to the point we

felt he was being picked on us or didn’t like us. One day I came to the Dojo and Shabazz was inside talking to some young ladies. As soon as I enter the Dojo, he got on my case about bowing wrong, without explaining what I was doing

wrong, he kept yelling at me to do it again (bow). The female visitors were laughing and Shabazz did not say anything to them. Being young and ignorant, I took it as Shabazz was trying to impress the young ladies or show off his authority.

My emotions got the best of me and I challenge him to a fight. He immediately expelled me from the Dojo. I don’t know why he just didn’t kick my ass. God knows I could’ve used a good butt whopping. Nevertheless, I ‘ve always felt bad

about what happen and wanted to make amends, but my ego wouldn’t allow me. Years later, when I matured in age, I wholeheartedly apologized to him.

Shabazz ran into some personal problems and close the school. By now Adriel was a black belt and I followed him. He began instructing a small group of street kids, which included me. Throughout the years we trained in such places as his

basement, church basement, Broadway Bank Platform, Martin Luther King Middle School and P.S. # 30 gymnasiums. Eventually, we were dubbed the “Dirty Dozen,” because we trained a lot and were prohibited from washing our belts. Some

students took it to another level and barely washed their uniforms. Our uniforms were ripped or patched and stained with blood and soil. Adriel eventually opened several schools that didn’t last. His type of training wasn’t for everybody, as

it was a bit crazy. We would do the 3 K’s, but it was much more intense. Each part lasted about an hour, so we would train about three hours a day. I recall doing the same “exact” basics every day for six years straight. He had a stick he used

to hit us with if we came up in our stances or slacked in class. At times, students would hide the stick, but it only angered him more, and the whole class paid the price. One time he actually broke it on me. As a form of punishment, we

would have to sweep the Dojo floor with a tooth brush, or hold a push up position on our knuckles, on two bricks with sand paper with a small candle lit beneath us. Fortunately, we were able to save ourselves from getting burn. In the

summer, he would put on the heat, to test our fortitude. Many students would pass out and we would simply grab them by their feet, drag them outside, throw water on them, and just leave them there until class was done. If someone got

hurt during sparring, he would put multiple people on them. I once was sparring with a purple belt student called Edison who had excellent kicks and he caught me on the nose with a spinning hook kick. Adriel put two other students on me,

and I was fighting all three students at the same time, while blood was gushing out of my nose. When we were done it look like a massacre had occurred. By no means do I encourage this type of training for anyone. We were young, dumb,

and full of testosterone.

Adriel has always felt the need to be under somebody. So, he sought leadership under Derrick Williams, Shihan of the Bronx Shotokan Karate club. He then mandated we wear their patch and train at their Honbu (headquarters) every

Saturday. I was totally against it at the beginning, but in Karate and especially under Adriel there’s no democracy. You do what you’re told and that’s it. The Honbu was not what I envision a Honbu to be. It was literally a small storage room

at some complex (projects) on 3rd Ave in the Bronx; a concrete box if you will, with no bathroom. Nevertheless, training under Derrick Williams, Shihan at the Honbu was a great and different experience. The Dojo was so small that basics

were done from a stationary position and not up and down the Dojo floor as I was accustomed to. He introduced us to different types of basics and calisthenics. Some I enjoyed and some I didn’t, like wrist push up. I was never able to grasp

the wrist push-ups, as my wrists could not bend back that far. Their forms were also slightly different from ours. That is when I realized there were different types of Shotokan. Derrick’s seem more J.K.A. based. Adriel adopted some of these

changes and began implementing them in our training. What impressed me most about training there was the quality of his students. They were all exceptionally good and had Great Spirit. I was proud to be a part of them.

I tested for my brown under Adriel and remained a brown belt for four years. Under his tutelage we were forbidden to ask for rank, and he tested us when he saw fit. After one very intense class, Adriel Muniz took off his worn out Black belt,

unfastened my brown belt, tied his smelly belt around me and announced in class, he hereby awards me Shodan (1st degree). It couldn’t get any more informal then that, but I was still very honored to get his smelly, dingy, rag of belt after

eight years of training in Shotokan, six with him. In Adriel’s martial art career, he only promoted three black belts: Jose DiCervo, Calvin Rodriguez and me. I was his first, Jose his second and Calvin his third. Of the three, I was the only one

who stood with him to the end. I got up to Sandan (3rd degree) with Adriel, though he had offered me fourth and fifth, in which I declined, as he was going through some personal problems at the time and was not in the right frame of mind.

Eventually, after 16 years of training in Shotokan I was presented an honorary Godan (5th degree) by Reno Morales, Hanshi of the “Original Bronx Shotokan Karate Club. I was touched by his generosity, but I’m not one who needs rank to

show my worth. Nonetheless, I humbly accepted it.

Adriel instilled in his students “Tokon” (fighting spirit) and “Oshi Shinobu” (Push and endure), but his training was all physical and he rarely touched on the philosophical and spiritual aspect of the martial arts, because of this many of his

students were unbalanced, and fell victim to their environment, including Adriel and I. Though Karate did not save everybody, it saved me. If not for Karate, there’s no telling where or how I would’ve ended up. I had my share of close calls,

but Karate was always something I could turn to when life in the hood got too hectic.

After Adriel, I tried Judo under Tony Camal in West Paterson. The constant throwing had me concern about injuring my back, so I dropped out. Then I tried Goju-ryu under Rich Rohrman of Budo-kai in River Edge, NJ. I wore a white belt to

class and he told me to wear my black belt. I told him, I rather be a white belt in a style I knew nothing of, than a black belt, but he wasn’t having any of it. I still train there from time to time, more so as a place to go to train with different

people. Throughout my years of training, I’ve learn the most from my students. Seeing what they do and don’t do right in class taught me how to teach and how to teach it. Under Adriel Muniz I did a lot of teaching, he often went through

phases were he just wouldn’t show up and I was left with the responsibility of teaching and like my old instructor Shabazz, I was a seasoned instructor by the time I reached Shodan.

Martialforce.com: Did you participate in other sports in school?

JUAN PEREZ: In high school, I tried wrestling and cross country, but quickly lost interest.

Martialforce.com: Are you a traditionalist, why do you think it is so important to practice and teach traditionally?

JUAN PEREZ: I’m not sure if any instructor of Japanese Karate can lay claim to being a traditionalist, especially if he or she is a Shotokan stylist. Gichin Funakoshi is widely recognized as the founder of modern-day Karate. His style became

known as Shotokan. Claiming to be a traditionalist of a modern style is like Jumbo Shrimp; an oxymoron. Nevertheless, it’s just my view and I’m not an authoritative figure on the martial arts.

Martialforce.com: Is it important as a teacher to study another style of Martial Art or to concentrate on their chosen style?

JUAN PEREZ: The aim should be for any martial artist is to master one style (though we can never), but look for things in other styles to enhance your styles.

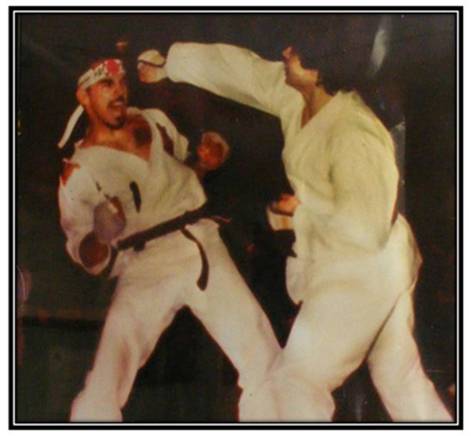

Martialforce.com: Give us a snapshot of when you competed, where at what age and some of the challenges you may have faced. How you may have overcome them?

JUAN PEREZ: I’ve competed in many tournaments, both Traditional and Open. I was what you would call a triple treat, because I did all three events: Kata, Kumite, Kobudo. I usually placed in the top three. I excelled in Kata, then weapons

and last Kumite, in that order. I won the New Jersey Semi-contact kumite title as a brown belt in a close match over the then reigning Champ Tamir Green. I’ve never won any Grand Championship title as an under rank, but won some as a

Black belt. My toughest competition was with myself, though some worthy mentions are Tamir Green and Jamal “G-man” Pearson. A knee injury forced me into retirement. At the time, I had won over 115 awards. I did one comeback after

an 18 years hiatus and competed only in Kumite at a traditional tournament in NY, in which I took first place.

Martialforce.com: You have a tremendous success at developing state, regional, and national champions, what is it about the way you teach that enables this success?

JUAN PEREZ: I’ve produced multiple states, regional, national and world champions. I don’t teach and train my students for tournament. In fact, most of my students do not compete. I just aim to teach good karate.

Shihan Juan Perez with student Sensei Joey Castro

Martialforce.com: What aspects do you feel an instructor must have to be a good teacher?

JUAN PEREZ: An instructor must understand that not all students are going to be champions. You’re going to have good students and you’re going to have those students who you are going question (to yourself) “why they’re even training?”

My experience has taught me, never to give up on those students who make teaching difficult; aside from teaching you patience, they may one day turn a leaf. I have had some of my worse students become my best students. Also, when

teaching in a group settling, you’re dealing with multiple personalities. Therefore, you can’t teach everyone the same. You’re going to have to learn who you can push and who you can’t. Not everybody is receptive to screaming and yelling.

You’re going to have students who you have to be a lot gentler with. People learn different ways. Only through time and experience you’ll learn who you can push or can’t.

Martialforce.com: How do you deal with the fear of fighting someone heavier or bigger, stronger?

JUAN PEREZ: First, if you’re true in your training, it will give you the confidence to face your fears. If you’re slacking in training, then you begin to question yourself and not face your fears. Also by doing the things you fear will take away that

fear. So, if your fear is that one day you may have to face someone who is bigger or stronger than you, so why not spar in dojo (where it is controlled) with someone who is bigger or stronger than you. But what I really try to instill in my

students is to practice “Bu.” The Kanji (Sino-Japanese ideogram) for “Bu” is often translated to mean “war, combat, or martial” and suggest a confrontation. But in actuality it means to “Stop” or “Avoid” a confrontation and the way you

practice Bu is by avoiding persons, places or things that may get you into a confrontation, even if it means you have to walk ten miles the opposite way.

Martialforce.com: How would you respond to those who say karate does not prepare you for the reality of the street?

JUAN PEREZ: Well, depends on why you are practicing Karate. If you are practicing Karate for recreational reasons, physical fitness or just to be part of a group, it’s likely it won’t work in the streets. Karate has all the tools necessary for

someone to defend themselves in the street, but if your approach to training is one of the above, it likely won’t work for you. Also, Karate is about the element of surprise. It works best as self-defense and not a one-on-one street fight. In

other words, if you’re getting mugged by somebody in the street, you eye gouge or kick him in the groin as quick and hard as you can when he least expects it.

Basics are a very important aspect of training for Karate and sports in general. When I trained under Seifullah Ali Shabazz and Adriel Muniz classes consisted of the 3 K’s; basics (kihon), forms, (kata) and sparring (kumite). 70% for the training

was focused on basics, and yet we excelled in all 3 K’s. The basics (kihon) consisted of the following:

Horse riding stance (kiba dachi) with the following punches:

Front stance (zenkutsu dachi) with a down block (gedan barai), executing the following punches:

Free fighting stance (jiyu kumite dachi) with a middle level posture (chudan gamae), executing following techniques:

A lot of time and energy went into these few basics. To earn a black belt (kuro obi) under them we had to master these basics. It took me eight years to get my black belt and for eight years straight I did these same exact basics every time I

attended class. You would think after so many years of doing the same basics you would be performing to their satisfaction, but that was never the case. We never got praise, it was always, “toes in,” “knees out,” “more power and/or focus

(kime)” and “one more time, one more time (mo ichido!)” Now 40 years later, I’m still doing and teaching these same exact basics.

There’s a misconception that you need to learn a lot of different basics to be a master in Karate. If you’re into mastering then less in best! A good example is, if I have two students and I teach one student (deshi) one basic and the other

student, 20 basics, then have them drill their basics for a year straight, which student do you think will have the better basics? This is traditional (dento) Karate. You take one basic or technique (waza) and drill over and over again, till you

can do it at the key moments without thought (mushin). I call it “sharping the saw.” In class I try to instill this principle to my students.

Kids have a short attention span, and they get bored easily. So, I had to come up with inventive ways to teach them these same few basics, without them getting bore. I’ll take one basic, (let’s say a front kick) and drill it all kind of different ways, for example:

Then I’ll have them do our beginner kata (taikyoku shodan) with front kick, instead of the customary lunge punch. We’ll do some fighting drills with the front kick and then end class with exercises that incorporates the front kick. So we just

did one basics, a bunch of different ways, and we’ll return to it again several times within the month.

I tell my students, if you’re itching to learn something new every time you come to class, then you’re not into mastery. As the old saying goes:

“Jack of all trades, master of none”

Its best to take a few techniques that fits your style and body type. Study them deeply and drill them like basics, over, over again, till they become second nature and you can do them at the key moments without thought.

As students of Karate-do our goal should be to be physically, spiritually and mentally balanced. The practice of Karate is the vehicle, or the way you’ll achieve those goals. It is true that most people joined or get into Karate for its physical

benefits. However, a good instructor (Sensei) will show and teach his students that there is more to Karate then just kicking and punching. Karate-do means “the Way of Empty Hand(s)”. The ideograph (Kanji) “Do” (The Way) implies that

the art is a way of life (geido) with moral and ethical principles one must adhere to. Sort of, like a religion, but without the worshipping of a particular god, unless one chooses to. The hard physical training that one should encounter in a

traditional Karate school (dojo), is what I’ve had stated previously, the “vehicle” to getting you balanced; spiritually, mentally and physically. It is only through physical exertion that the mind, body and spirit are truly challenged, and thus,

nourished and grows.

Martialforce.com: What advice would you give someone that is thinking about training in Karate but isn’t sure?

JUAN PEREZ: First, I’ll ask them what brings them to Karate, and then explain how Karate may benefit them. Then I’ll tell them try a class, they have nothing to lose, the first class is free, with no commitment what-so-ever.

It is important to note that people get into Karate for various reasons. Unfortunately, many teachers think that it should be for one reason…. their reason! I’ve discovered that, although Karate cannot cater to everyone individual needs, it can

broadly be practice for three distinct reasons:

Fortunately, traditional Karate (Dento Karate) can be practice for all three, without making any real changes or adjustments to the class curriculum. I tell my students, if you want to be healthy and in shape(Kenko), a champion, or

competitive (Kyogi), physically, spiritually and mentally balanced (Budo), the key is “come to class and train with a purpose!” Whatever is the motivating factor (Hosshin) that brought them to Karate, they can achieve by being true to

their Karate and their Karate will be true to them! “True” in the sense of dedicating oneself to their craft, by training diligently and with a purpose.

Martialforce.com: What is the definition of a good Sensei and how would you define a good student?

JUAN PEREZ: I think this question warrants an explanation of what the term actually means. If you look up the word “Sensei” it will note that it is a Japanese honorific title. The term is written with two Sino-Japanese ideographs known in

Japanese (Nihongo) as Kanji. Each ideograph has an ancient Chinese reading (On’yomi) and a Japanese reading (Kun’yomi). The first syllable “Sen” is the Japanese reading of an ideograph that renders as “Before”. The second syllable “Sei”

is the Japanese reading of an ideograph that renders as “Life.” When combined and depending on how it’s used, can roughly translate as:

“One who has gone

before (in life)”

This does not imply to chronological age, but in knowledge. Basically,

a Sensei is someone who’s “been there and done that.” If you want to add a

more flowerily meaning to the term then a Sensei is someone who is ahead of

you in the

journey we call “Way of Empty Hand” (Karate-do), or it is someone who points to that way of life. This is why a Sensei is not just a person who instructs Karate techniques, but more so the one who leads “the way” (Do) by example. This

is the technical

definition of the term.

My interpretation of a Sensei is not only someone who is ahead of

someone else (say, in knowledge of the art), but someone who can acknowledge

he or she still have much to learn. ASensei does not have all the

answers, and those who

claim they do, are

nothing more than a “mouth warriors” (Kuchi Bushi).

It is impossible to know everything about Karate, because Karate parallels

with life. The more you grow in life, the more you need to learn. I’ve

discovered that the more I learn, the more I realized how little I

know. Therefore, a Sensei to

me is first and

foremost a student (Deshi) of the art (Gei).

I have to say as a Sensei, I’ve learned more from my students, than I

did from any instructor, book or video I had. It is through carefully

observing them that I’ve learned to teach the do’s and don’ts of Karate. Students

are the real

teachers of Karate.

I would also like to add that here in the West, there is a big misconception

that once someone attain their black belt (Kuro obi) it automatically

makes them a Sensei. Nothing can be further from the truth. A Sensei in Karate is

a "teacher" of a school, who must be at least a 3rd degree (Sandan) level. A black belt recipient is known as a “Yudansha”. In Japan, the word Sensei is also used as a title to refer to or address other professionals or persons of authority,

such as:

Maintenance person

A good student understands that their measly monthly tuition doesn’t pay for

their lessons. It just keeps the doors open. You cannot put a price on

knowledge. The stuff my students learn will stay with them for the rest of

their

life. Because I

just don’t teach Karate, I teach life skills.

Nevertheless, I’ve heard many instructors say their worse students are

their black belts. When I first started teaching, Grand Master Lou Ferrer

once said to me, “When he promotes someone to black belt, he’ll usually

throw them out of the

school, because they’re the worst students you can have.” At first, I thought he was kiddin' or slightly exaggerating. But then I discovered he wasn’t playing. Now, I’m not saying my worse students are my black belts, but I can kinda

understand where he was coming from. At that level, they lose their “beginners mind” (Shoshin)and think they know it all. Often times, you can’t rely on them like you used to and many of them have inflated egos. Fortunately for me, I

had far less than more of these types of black belts. I think it’s because, I have so few black belts. Of the 40 plus years I’ve been teaching, I’ve only promoted 11 black belts. I seldom award a black belt. If someone is looking to get a

black belt from me, they’ve come to the wrong place. I’ve had students leave and go elsewhere just to get their black belt, because I wouldn’t give it to them. That being said, tells you why I wouldn’t. If they’re like that now, can you

imagine how they’ll be if

they got their black belt.

Also, champion students are more often “not” your ideal good student, and although they may bring glory and pride to the school, they can be problematic. Especially, if they're kids, then you have deal with soccer parents. I’ve thrown many

champion kids out of my school, because of their parents. These parents feel the school should revolve around their kids, they try to tell you how to do your job and dictate what goes on in the school. They forget who made their child a

champion. They quickly find out when I throw them out, and they go somewhere else, only to see their kid deteriorating and losing in tournaments. All of suddenly, the grass is not so green on the other side, as they thought. In fact, it has

weeds. Most try to come back, to no avail. I let my students know from the door, “if they're un-happy here, for whatever reason, feel free to try somewhere else. They're welcome to come back, as long as they don't leave on bad terms. If I

have to throw you out, then you're not welcomed back!

Martialforce.com: Regarding the competitive arena. What are the differences if any that you have witness in tournament whether positive or negative?

JUAN PEREZ: My school (dojo) does both open (all styles) and traditional (dento) karate competitions. In the open circuit the quality of form (kata) competitors has declined dramatically. Their forms at best are poor, sloppy and have no

substance. It’s become a matter of who can scream the loudest and make their butt touch the floor with their exaggerated low stances. As for sparring (kumite), it’s become a game of tag, but I have to say, the foot work and athleticism of

some of these open fighters are amazing. In the open circuit anyone can compete at their “World Level Tournaments” as long as they’re willing to pay their own traveling and entry expenses. Also, there World Level Competition is mainly

against Canada, and to a lesser extent Mexico, Guatemala and possibly England. I hear now, Ireland and Italy have been added to the mix. The open circuit has more world champions than any other circuit in the world. I once saw someone

at one of these events with a jacket and baseball cap boasting he was a “World Champion.” He took off his jacket and had on a sweat shirt printed with the same thing. He took off his sweat shirt and had on T-shirt printed with the same

thing. Then he changed into his uniform (gi) and on the back of his uniform was (you guess it) the same thing, he even had it embroidered on his belt (obi). Then I looked at his belt and it was tied wrong. How can one claim to be a “World

Champ” and don’t even know how to tie their belt?

In the traditional circuit the form competitors are much cleaner and crisper, but it has become a matter of long pauses and at times, the kata may come off a bit bland. There’s no individuality, or putting one’s own flavor (sazon’) into a form in

the traditional circuit, as is in the open circuit, which I don’t necessarily agree with. Now, I’m not implying changing a form, I’m totally against that - leave that to the open competitors. I’m just simply suggesting a little creativity in the tempo

and execution of the form would be nice. Nevertheless, at the elite level, the traditional forms are much more explosive and dynamic. In traditional fighting, kicks and take downs (sweep or throw) score more points. A kick to the head is 3

points and to the body two points. So there’s much more kicking, then in the pass. Sweeps and take downs are also 3 points. These days, you’re more likely to be score on with a hook kick to the head (jodan ura mawashi geri) followed by a

hip throw (ippon seoi nage), than a middle level reserve punch (chudan gyaku zuki) with a foot sweep (ashi barai) like in the old days. The traditional fighters are much more versatile then in the pass, but the game has gotten too soft. There

are too many rules and the competitors must wear unnecessary safety gear, like chest protector for men. Sad!

In the traditional circuit, to compete at the world level one must qualify, by first “winning” the states, regional, national championships of their sanctioning body. Then they must try-out for the USA team and if they make it, they’ll first get to

represent the USA at the Pan-Am games and if they do well there they’re qualifying to compete at the world level. The World Karate Federation is the cream of the crop. This league boasts 130-member countries. The World Karate

Federation Championships are held every two years in different parts of the world. It’s considered a great honor and accomplishment just to be able to make it to this level. Only the most seasoned, proven competitors from each country are

allowed to compete at this event. It should be noted that the Japan Karate Association (JKA) helped form this league, but eventually pulled out, because the Japanese were getting their butts handed to them by the Europeans. The Japanese

felt that if they keep losing to the Europeans, no one would want to learn karate from them, so the JKA withdrew from this league and started their own (biases) World Championships where the Japanese are almost always guarantee to win at

their event. In the WKF, Europe has done well. England, Spain, France and Italy were the top countries for many years. Now, Middle Eastern countries, like Iran, Turkey and Egypt are dominating. Japan is also now a strong country, even

though the JKA don’t participate at these events. America has always been at the bottom of the barrel. I once had a European student who came straight off the boat from Slovakia, and she said that in her country they make fun of

American karate. That wasn’t the first or last time I heard that. Apparently, we have the worse karate in the world. Tokey Hill was the first American to win a gold medal in 1980. At the time, the WKF was known as WUKO, and was not as

big as it is today. Some claim a female had won gold for USA prior to Tokey Hill, but she got no recognition because of her gender. Nevertheless, it would take 22 years for an American to win a gold medal again, which was succeeded by two

Asian-American; George Kotaka and Elisa Au of Hawaii.

It should be noted that some countries have an advantage over USA, because their government pays their athletes to train and compete. Nothing comes out of their pocket and their sole job is to train and represent their country at the highest

level. In Japan, some jobs have an athletic department, where an employee works half-a-day and train for the other half. Multiple World Kata Champion “Atsuko Wakai” stated that she was very fortunate that her job had a karate program that

allowed her to worked half a day and trained for the other half and she got paid full time. She claims she wouldn’t have been able to win consecutive world kata titles, if it wasn’t for this. Here in America, our athletes have to pay for all their

training and traveling expenses out of their own pocket and some have to work two jobs to do so. For an American to be able to compete at the highest level in the traditional circuit, they must be multi-task, unless they’re wealthy. When

Elisa Au won her first gold medal, she did it while working a full time job, going to school, teaching karate and training for competition. And I believe the second time she even juggled a family. It takes a special kind type of person to be able

to do that.

Martialforce.com: If you could go back in time and speak to a younger version of yourself, what advice would you give him and why?

JUAN PEREZ: Take full responsibility for yourself. Up until my early 30’s, I blame the government, my race, my up-bringing, my abusive father and whatever else I can for the crap that went on in my life. When I took full responsibility for

myself, I was able to make a 360 and change my life for the better. Circumstances will arise that we have no control over, and cannot change, but I learned we can always change how we respond to them. I may have not been able to stop my

abusive alcoholic father from beating me, but I was able to use that to teach me how “not to be” as a father. Because of him, I became a good father to my kids. This was something I needed to go through to teach me some valuable lessons.

Just like Jesus Christ died on the cross for our sins. I suffered beatings, so that my kids didn’t have to, and hopefully future generations.

The mental and physical abuse I encounter was a cycle I was able to break when I took responsibility for my life. I learned not to hold my father accountable for his ignorance, as he was just doing what he was taught and experienced in the

hands of his own father. My story is not unique, as many Puerto Rican families hit their kids when they act up, or least in my inner circle. But when you add liquor to the mix, it doesn’t take much for a beaten to ignite and the beaten is taken

to a whole new level. I recall the effects of waking up to belt lashes on my face and body. Nevertheless, I learned how to take full responsibility for my life and respond to the things I cannot change in a positive light to make me a better

person. This is just one of many lessons I’ve learned by taking full responsibility for myself.

As for a Karate-ka, I would tell a younger version of myself to get in the best physical shape you can and aim to become a great athlete, oppose to just a Karate-ka. I’ve competed in hundreds of tournaments and done well. But I must confess,

I was never truly in the best shape I could’ve been in and aside from Karate, there was not any other sport I was good in. Had I been in peak performance shape, and became a great athlete, there would’ve been no limit in what I could’ve

accomplished and excelled in. A great Karate-ka is just that (a Karate-ka). A great athlete can excel in multiple sports. The former great middle weight champion of the world Roy Jones was a great example. He was a great athlete who

became a great boxer, and was also an elite basketball and baseball player. Most great Karate masters only excelled in Karate, and although there’s nothing wrong with that, my focus would have been to become a great athlete first, and

then Karate-ka that way my options would have been greater.

Martialforce.com: As a martial artist, what achievement are you most proud of?

JUAN PEREZ: Earning my black belt (Kuro-obi) was perhaps the achievement I was most proud of. It took eight long years to earn my black belt, not by choice. We were forbidden to ask for rank and it was up to my instructor (Sensei)

discretion when he saw us fit to test. However, I never tested for my black belt, or perhaps I didn’t know it was a test. He awarded me 1st degree (Shodan) after a long hard training session, which concluded with him taking off his dingy belt

(Obi), and tying it on me and then retorting to the class, “I hereby award you 1st degree!” I was going on my fourth year as a brown belt (Cha-obi) when he awarded me his belt. What I recall the most about that day was how bad his belt

smelled. We were also forbidden from washing our belts, and this belt had years and years of sweat embedded in its very fiber. Nevertheless, it was great honor.

Martialforce.com: What would you like to accomplish in this lifetime in regard to martial arts or life in general?

JUAN PEREZ: My lifelong goal has always been to be physically, spiritually, mentally and emotionally balanced. I have not been able to accomplish all four at the same time. When I’m good in one area, I tend to slack in another area. This

has been an on-going problem for me that I have not found the solution for. I think it’s the man in me that doesn’t allow me to concentrate on two things at the same time. Nevertheless, this is the goal I want to achieve before I die.

Martialforce.com: At this time, we here at Martialforce.com want to thank you for sharing your martial arts journey with us. We wish you future success in all your endeavors.

JUAN PEREZ: Thank you for the opportunity to express my thoughts.